Camembert President

LA CAMPAGNE NUMERO DEUX (27 weeks/190 days until Emmanuel Macron’s reelection) : Why do we, French people, care so much about the presidential election — and why it all goes back to cheese.

France is a monarchy that undergoes a succession crisis every five years, by way of an election.

It is by design. Under France’s current constitutional arrangement, the so-called Fifth Republic, the sole real seat of power is the office of the presidency. It is therefore unsurprising that all civic and political life would revolve around it.

The great historian Marcel Gauchet observed in a recent radio interview that the immense powers of the French presidency were specifically tailored for a man, De Gaulle, of equally immense legitimacy. De Gaulle drew his stature from his leading role in the resistance against the Nazis during World War II. Even his most acerbic critics, among them François Mitterrand, acknowledged not only De Gaulle's foresight but also his actions. He had been on the right side of history and then he had willed and organized the resurgence of France almost out of nothing. In a sense, only a character as epic as De Gaulle was big enough for the monarchical institutions of the Fifth Republic.

De Gaulle himself had thought up the election of the President by popular vote. In its first 1958 version, the Fifth Republic Constitution entrusted the election of the President to a college of about 80,000 electors (“grands électeurs”), made up of all of France’s elected officials. On December 21st 1958, De Gaulle became the first and only French President ever designated by such a scheme, and with a Soviet score I might add (78,51%).

To his credit, despite having grown up in a monarchist milieu, De Gaulle believed in democracy. He just did not believe in parliamentary democracy. Throughout his life he had held a dim view and an abiding suspicion of the legislative branch. After all, back in 1940, the Parliament had voted full dictatorial powers to the ignoble Pétain and thus sold the République away to the Nazis. De Gaulle considered, rightly or wrongly, that legislative bodies were too fickle and too chaotic, and even worse: they were amenable to be taken over by Communist majorities – and who would want that?

In 1962 De Gaulle had another problem on his hands: his legislative majority, although enormous, was an unwieldy and unreliable alliance. His own party, UNR, did not control parliament. He had opted for a referendum to ratify the Évian accords with the Algerian Provisional Government, in part because he could not trust right-wing MPs on the issue of peace and Algerian independence.

The final conclusion of the Algerian crisis promised a return to the more regular state of affairs, where Parliament would reassert its sway and its full powers of nuisance. It was the end of De Gaulle’s de facto free rein. It became apparent to De Gaulle that the rowdy and splintered legislators were not keen to follow his lead. The Constitution of 1958 had failed to solve the quandary that had brought it into existence in the first place: government weakness and instability stemming from a fractious parliament.

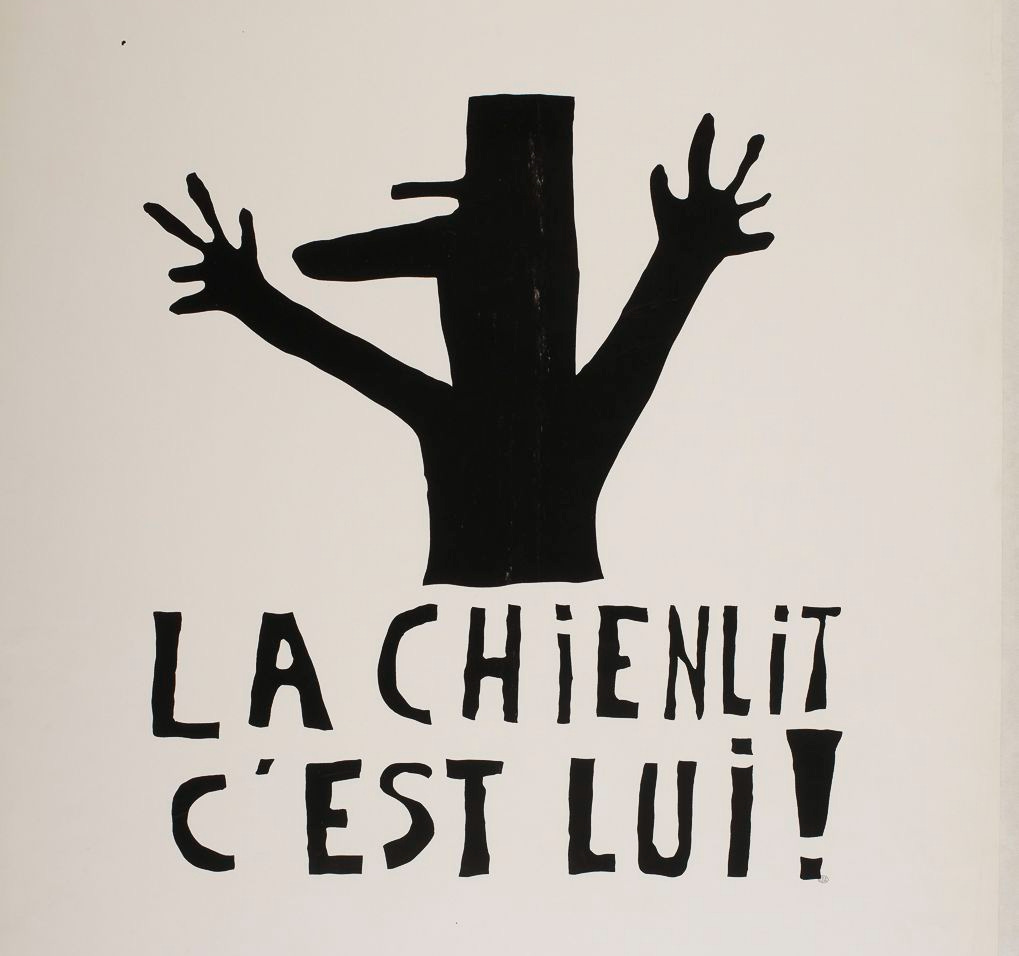

In late September 1962, De Gaulle went on the offensive. He announced yet another referendum, this time to modify the Constitution to allow the election of the President by universal suffrage. It was like a bomb went off inside both chambers of parliament. To this day, the legality of that referendum remains highly dubious. Gaston Monnerville, the President of the Senate and definitely not a radical firebrand, accused De Gaulle of “forfaiture” (an abuse of power) and hinted that he should resign or be arrested.

You might wonder: why would electing the President by popular vote be such a big deal? After all, this is how things are done in the United States (at least technically). The key difference of course is that in the US the President cannot dissolve Congress at his or her leisure. The legislative and the executive branches are co-equal. In effect De Gaulle’s constitutional reform aimed to neuter, if not destroy, the legislative branch. It did keep Parliament alive but in name only, as an empty shell.

MPs were fully aware of that. And for the only time in the history of the Fifth Republic a vote of no confidence passed (the motion de censure), leading to the fall of the government on October 4th 1962. It was the last time a French parliament truly exercised its powers, on the cusp of losing them all. For reference, the right wing held a majority of 489 in a chamber of 576 members.

The government fell but De Gaulle won his referendum. And so began the second Fifth Republic, or what some have called the post-Algerian Fifth Republic.

“How can you govern a country that sports 258 varieties of cheese?” De Gaulle had once quipped. The quote may be apocryphal but it captures the essence of the Général’s theory of governance. It points to the fragmentation and to the centrifugal forces that stirred in French society. In his experience, if the myriad of local and class interests that make up France were given legislative representation and power, nothing could ever get accomplished. At heart, his was a pessimistic view of France’s political culture and civic life, but one that was not necessarily unfounded. Don’t forget, parliamentary rule had failed not once but twice in the span of two short decades, in 1940 and in 1958. Both times De Gaulle had ridden to the rescue (in somewhat ambiguous circumstances in 1958, but that’s for another post). Say what you will about the tenets of Gaullism, but the man had a point.

His solution was elective monarchy. It was the only logical way to maintain democratic legitimacy and democratic institutions while curbing the parliament’s proclivity to internecine chaos and gridlock.

That not-so-minute tweak fundamentally reshaped France. The office of the presidency grew to become a monstrous, shimmering astral object that sits at the center of it all and orders the motions of the lesser bodies around itself. In France the President truly is the Roi-Soleil, the Sun-King, just by virtue of what you may call political gravity. There is a reason why the often petulant Macron calls himself Jupiter. It rings somewhat ridiculous and orotund. It also happens to be correct.

The powers of the President are not broad sui generis. The President is Jupiter because De Gaulle deliberately strangled the legislative branch. Compared to the presidency, everything else, every other elective position, parliament, big city, small city, region, department etc – all this is a sideshow or a stepping stone. If your goal is to enact your political vision or your policy agenda, left, right or centrist, there is only one place, and that place is the Presidency. The rest is irrelevant, or rather it is only relevant insofar as it allows you to build notoriety, influence, a clientèle or a party faction, which may then earn you a portfolio in the government, proximity to the monarch-President and eventually, the supreme office itself.

Like in any monarchy, succession is one, if not the monarch’s central concern — but also that of his courtiers, of his sworn enemies and of all the usual cast of rumor-mongers, reprobates, prospective turncoats and budding traitors. And because it is an elective monarchy rather than a dynastic one, the public plays the pivotal role in that recurring high-stakes drama. It is Games of Throne and Lord of the Flies and Survivor, but in real life and with real consequences.

A presidential campaign is always a knife fight, cruel and operatic. Blood is spilled, hopes are crushed, and in the end the voters give their thumbs up or down. To the victor the spoils and woe unto the vanquished, vae victis.

Nowadays it is fashionable among French pundits to wail about France’s crisis of representation, or to bemoan the feckless “corps intermédiaires” — the institutions supposed to represent people’s political interests. According to their diagnosis, it is the reason why the French routinely take to the streets to demonstrate en masse, because that is the only way those in charge, the politicians, will consider their demands. You often hear the same pundits tut-tut demonstrators with a straight face, explaining that demonstrations are either a failure of democracy or even that they are by their very nature anti-democratic, the dreaded rule of the mob.

Their stance is both facile and mendacious. De Gaulle twisted the Fifth Republic to quash political representation. That was his purpose when he muscled through the election of the President by popular vote. Everybody knew it then, and the majority even voted for it.

In a system where the elected President is Jupiter, politics can only be a confrontation between executive power, the government, and its subjects. That configuration, that political dynamic, taps into something very primal and atavistic in the French citizenry. We have not forgotten the revolutions of the past – we are taught in school from an early age to treat our rulers as servants and not the other way around. We are also taught that the National Assembly, wherever and whenever it is convened, is the nation and the carrier of the general will. And yet, under De Gaulle's Republic, the National Assembly has no power to speak of. It has even less power now that the presidential term has been reduced to five years, thus coinciding with the full duration of a legislature. Parliament is so thoroughly debased it is a mere appendage of the periodic presidential plebiscite. De Gaulle created that perpetual contradiction: L’Etat c’est moi says the President, NOT! yell back the people.

The strangest thing, and no doubt the most disappointing to pundits, is that French voters seem to like it that way. The presidential election consistently registers the highest turnout of all elections. People know it is the only election that really matters, and they use it as an opportunity to count themselves, that is, the relative size and power of their parties or factions, and yes, to protest. In that sense, France’s presidential election is also a form of mass demonstration, the ultimate form of mob rule.

IT HAPPENED

Last night (October 14) the Socialist Party officially nominated Anne Hidalgo as its candidate to the presidency. It is the second time the Socialist Party has endorsed a woman, after Ségolène Royal in 2007. Progress is afoot.

Also on Thursday afternoon President Manu scored a goal on a penalty kick, at a charity match between Variété Club (celebrities team) and the Poissy hospital team. Although Manu was bestowed an honorary medical degree by his own minister of health, he played for the celebrities’ side.

Today’s song is Serge Gainsbourg’s version of the French national anthem, La Marseillaise.