Immigration in far-away France

What a tiny island in the Indian Ocean can tell us about the immigration question in France.

I started LA CAMPAGNE as an attempt to explore the difficult stuff. I try to bring to light salient aspects of French politics that are usually ignored by non-French media outlets. I also try to point to historical legacies that my own compatriotes fail to perceive, perhaps because these are more readily seen from afar.

Unsurprisingly, no political issue in France is more fraught with these unspoken or omitted realities than immigration. Immigration is the ultimate French refoulé, or repressed sentiment. Funnily enough, like a Freudian slip, “refouler” is the common verb that describes the administrative act of denying entry at the border.

Like boiling water overflows from under the lid of the pot, it is often at the margins that the repressed returns, and with a vengeance. Last week, on a campaign visit to the French départements of the Indian Ocean, aspiring presidential candidate Michel Barnier announced that he would abolish the droit du sol — birthright citizenship — on the island of Mayotte. This came and went barely noticed, and yet the département of Mayotte is a key place, a hinge where the future of what it means to be French is playing out before our eyes.

To disentangle Barnier’s proposal, we need to take a step back.

Contrary to the “great replacement” hustlers’ meretricious fantasies, it is well-documented that most migrant populations do not move very far. Unless organized by state actors, either to colonize distant countries or to bring in extra labor (forcibly or less forcibly), migrations remain local phenomena. The greater the distance, the greater the costs (monetary, dangers etc…) and in general migrant and displaced populations are not the most privileged. Case in point, of the estimated 6.7 million people who fled Syria in the past decade, most ended up in neighboring countries. Turkey received the majority (about 3.7M) while 850,000 went to Lebanon, 665,000 to Jordan and 245,000 to Irak. That Germany granted asylum to some half a million Syrian refugees was certainly generous but not nearly as impressive as what smaller and less fortunate nations have done.

When it comes to migrations, geography is destiny — and that is not limited to conflict zones or to the paltry 12 kilometers that separate Turkey from the Greek island of Lesbos (to where many Syrian refugees flocked). Take Canada for instance: while Canada is very proactive in attracting immigrants from all over the world, it still counts an estimated 1 Million US citizens on its soil (both dual citizens and permanent residents.) By some measures US citizens are Canada’s largest group of foreign origin. I say by some measures because border flows between the two countries are considerably easier and therefore more intense than say between Canada and China or between Canada and India. A common border, or at least relative geographic proximity, determines the size of migrant populations: despite the recent rise in sea crossings in the Mediterranean, the majority of migrants from African countries relocate to other African countries; by the same token Afghans go to Pakistan and Iran in much greater numbers than to European countries or the Americas. Only systematic, at-scale policy interventions can overcome vast geographic distances. Canada does it with purpose, taking advantage of its isolation and difficulty of access to pick and choose who can come in (preferably the young and the high-skilled.)

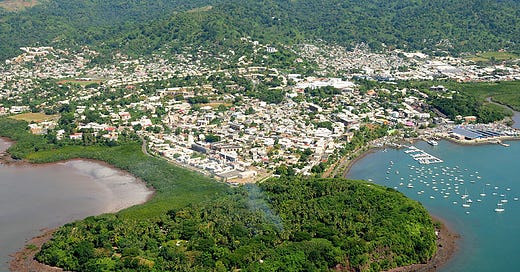

Which brings me to the beautiful, if incredibly complicated, island of Mayotte.

Mayotte is located in the Mozambique channel, just North of Madagascar. Historically and geographically it was part of the island sultanates of the Comoros. France purchased it in 1841 from Andriantsouly, its local prince of Malagasy descent. Eager to turn the island into an attractive destination for investors, the government of King Louis-Philippe abolished slavery in Mayotte in 1847, a full year before France abolished slavery for the second time in the French Antilles and in the Réunion island. The State indemnified the slave-owners at a rate of 200 francs per slave. Reparations, if you will.

In 1848 Mayotte was integrated into the young Second Republic. It later served as France’s base to conquer the other Comoros Islands (in 1886), thus solidifying the Republic’s strategic control over East African trade routes. Because of its anterior acquisition, Mayotte stayed under the direct administration of France through the early 20th century. The Mahorais, the inhabitants of Mayotte, created their own unique hybrid colonial identity — Muslim and French, speaking both the métropole’s language and shimahori, Mayotte’s variant of shikomori, the Swahili of the Comoros.

In 1946, at the end of the war, the Comoros protectorate was reorganized into a unified Territoire d’Outre-Mer that included Mayotte. In 1958, the territory voted down independence. Tensions continued to simmer between Mayotte and the other islands and came to a head in December 1974 when France, under pressure from the United Nations and Comorian independentists, organized a referendum on independence. 90% of Comorians voted “yes” while Mayotte voted “no” by 64%. Same country, same archipelago, same culture and language, completely opposite decision. After much wrangling, another referendum was held in February 1976, but only in Mayotte. 99% of Mahorais voted to stay within France. By then the Comoros were already an independent nation. Both the Comoros and the United Nation disputed the legality of that second referendum, and the Comoros continue to this day to claim sovereignty over Mayotte.

This is not without merit. Mayotte is 70 km away from the island of Anjouan, a mere 4 hours ride by kwassa-kwassa, the speedy boats used to make the passage. If that situation reminds you of Lesbos and Turkey it’s because it is very similar: geographic proximity governs migration flows. Mayotte is now a full French département. The far-away administrative border of the European Union splits the Comoros archipelago in two.

That is where the immigration problems begin.

Until 1995, in spite of constant frictions with the Comoros, people could freely move about the archipelago — as they had done for centuries. Residents of Mayotte had extended family on Anjouan, Grand Comore and Mohéli and vice versa. Ancient trade networks and island sociability had endured, regardless of political and administrative divisions. These old bonds began to fray as Mayotte fully benefitted from financial transfers from the métropole, while the Comoros were beset by chronic instability and post-colonial under-development. French mercenary Bob Denard, a man with deep ties to France’s secret services, was involved in 4 of the more than 20 coups d’état in the archipelago from 1975 until the present (several times with the support of his French government patrons). Serving and removing several presidents, he managed to amass considerable assets there, lording over the place through the 1980s like it were his own medieval fiefdom. Quite understandably, in light of such chaos, Comorians started to put down roots on nearby Mayotte and have children there, on French soil. French territory proper offered safety and markedly better opportunities than the French post-colonial failed State run by a gang of French brigands, often at the behest of France’s services.

To stem that flow of relocation, which strained the local economy, Mahorais elites and politicians lobbied the right-wing Balladur government for new visa requirements. Before 1995, 3-months visas were delivered automatically upon arrival, and often disregarded. In all but name it was legal for Comorians to travel to Mayotte and to stay there. Since 1995, Comorians need a visa to come to Mayotte. In other words, because of the accidents of colonial and post-colonial history, families and friends from the same country are now separated by a border. In consequence, Comorians in Mayotte are treated as illegal immigrants in their own ancestral motherland. Many will argue that the Mahorais chose to attach their destinies to France and too bad for the other Comorians. Maybe that’s a fair judgment, or maybe that’s an apology for colonization and rule by mercenaries. One way or the other, that does not help in the current predicament.

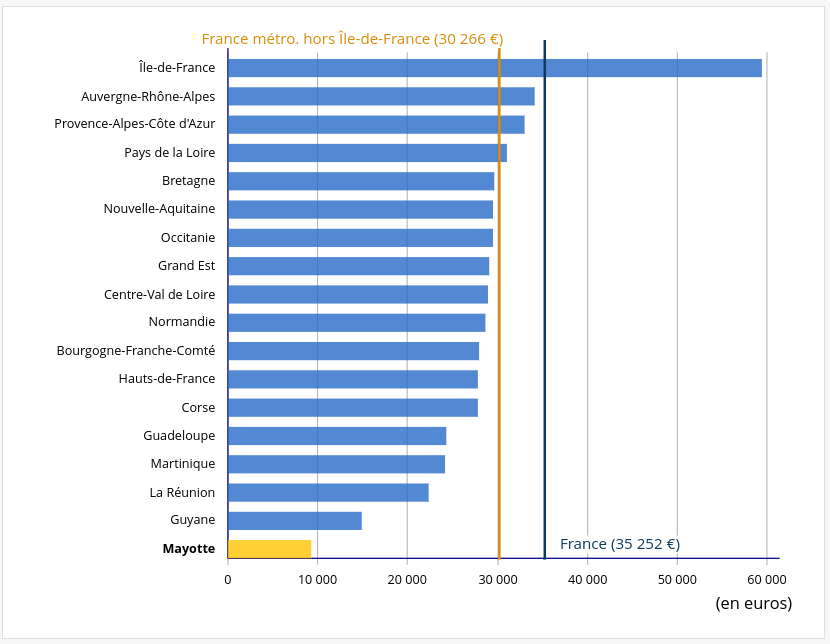

Mayotte’s GDP per capita is the lowest of all of France’s regions at €9250 (in 2018). It is almost 8 times higher than that of the neighboring Comoros islands.

In addition, Mayotte’s population is growing at an astounding rate: it went from 85,000 in 1985 to 255,000 in 2017. If it were a country, it would be the second fastest growing and youngest in all of Africa, only bested by Niger. INSEE, France’s statistics agency, estimates that Mayotte’s population could reach between 440,000 and 760,000 by 2050, depending on migrations. For reference Mayotte has roughly the same land area as Carson City, Nevada (144.7 square miles, population 55,000). In 2017, there were almost 10,000 births at Mamoudzou’s maternity ward. That’s 25 new babies a day. French hospitals do not ask for your papers.

It is believed that half of Mayotte’s current residents do not have French citizenship, although numbers are hard to come by. Of these non-French citizens, an estimated 30,000 residents are undocumented. That’s perhaps 5% of all the undocumented immigrants in all of France, concentrated in 375 square kilometers. That said, actual numbers are almost impossible to come by, and they are highly sensitive. We know that in 2019 there was 27,000 “refoulements” in Mayotte, almost all back to Comoros (compared to 19,000 from the métropole). In sum, the majority of expulsions from French territory take place in Mayotte.

The island département is unraveling. Kaweni, the largest shantytown in France, keeps growing on the verdant hills that surround Mamoudzou. 84% of the people in Mayotte live below the French poverty line. Infrastructures, from water mains, sewage and the power grid to schools and hospitals, were not built for that kind of demographic explosion. Crime and violence are rampant. In 2018, the French Mahorais went on strike and blocked the roads to clamor for help from the métropole. Some took to vigilantism and rampaged through Kaweni beating up the inhabitants and destroying their makeshift homes. These actions became known as “décasages” — from the old colonial idiom of “case,” the pejorative term for rural African houses. These are folks who share the same culture, who speak the same language and who may even have family ties if you go back three or four generations. They were just born on different sides of a new border. Geography is destiny or rather, tragedy.

In 2018 Thani Mohamed Soilihi, Senator (LREM) from Mayotte, introduced a law restricting birthright in the island. To claim French citizenship, any person born in Mayotte would have to show that at least one of their parent had been a legal resident for a minimum of 3 months at the time of birth. It passed in Parliament with Macron’s support, and the Constitutional Court gave its blessing to that breach of the principle of Republican equality on rather specious grounds. Then again, that's the final word. Quis custodiet ipsos custodes?

That law was written to dissuade those who live in Mayotte without papers, and those who cross from the Comoros, to give birth in Mayotte. Their children are now barred from obtaining French citizenship at 18. So far it's not clear that it had any discernable effect. Mamoudzou's maternity ward is as busy as ever. At this point, Senator Soilihi is floating an extension from three months to one year legal residency.

A reporter for France’s equivalent of CSPAN recently noted in a sibylline tone that the real effect of that law might lie elsewhere:

“…certains candidats pourraient défendre une profonde réforme du droit du sol pour l’ensemble du territoire français.”

(“…some candidates could propose a sweeping reform of birthright citizenship for French territory as a whole.”)

When Michel Barnier spoke of abolition of jus soli in Mayotte, he did not do so in a vacuum. In truth, this idea has been bouncing around the far and the not-so-far Right for decades, and not at all for Mayotte. Former President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing advocated for its abolition as far back as 1991. In 2013 Jean-François Copé, then President of the Gaullist UMP, came out in favor of sweeping reforms. A few weeks ago Marine Le Pen tweeted:

(“Abrogation of birthright, strict conditions of assimilation, forbidding ‘positive discrimination’ : we want to secure the right for the French people to remain itself.”)

Obviously, none of these people ever cared about Mayotte, a 95% Muslim fragment of France’s bygone empire lost in the Indian Ocean. But they care a lot about the so-called français de souche (literally, the tree-stump French, you get the picture) and they will not think twice about exploiting Mayotte’s intractable situation for their own ends.

In the long run the new law in Mayotte will produce a generation of undocumented people — Kafkaesque refugees in a country no longer their own, schooled in French schools but forever barred from becoming French citizens. Something will have to give somehow.

The solution cannot be found in Mayotte alone, and the Comoros deserve prosperity and stability as much as any other nation — especially after the role France played in its despoliation. Catching up will not be easy and the speck of France just beyond the horizon will retain its attraction for a while. Geography is destiny.

Back in the métropole, that same law may open new avenues for demagogues and vindictive ethno-nationalists to justify exceptions to rights that were settled long ago, and to radically alter the foundations of French citizenship. It will not be lost on anyone that thanks to minor historical coincidences, the proverbial foot in the door is provided to them by people they would readily exclude as Muslim invaders and unworthy of being French.

The mephitic Éric Zemmour has long fantasized about expelling the 5 Million Muslims living in France. And while he deemed such project unrealistic, he could not abstain from comparing it to the flight of France's colonists from Algeria — his pieds-noirs parents. His unresolved childhood traumas and his pathological thirst for revenge are all his, but France's colonial heritage is ours. We will not escape it and we must deal with it like adults, in Mayotte and in the métropole.

In the next post, I will explore immigration in the métropole.

À la prochaine ! — M.

Today’s song is “Musada” by Baco, the giant of Mahorais music — it kicks ass.