The Godfathers

LA CAMPAGNE NUMÉRO SIX: the 500 signatures ballot access rule and why it matters; 177 days until Macron's re-election,

In this installment of LA CAMPAGNE, we dwell on a bit of electoral law arcana. You'll see why.

A few key rules govern candidacies to the presidential election. The first and perhaps the most important is not often mentioned in the foreign press. To become a candidate to the French presidency, and therefore have ballots printed with your name on it, you must collect at least 500 signatures from elected officials (or “parrainages” in French.) These parrains, or godfathers, can be members of Parliament, senators, members of the European Parliament, regional and departmental conseillers, as well as mayors. No more than 10% of parrainages can come from the same single département, and the entire list must comprise signatures from at least 30 départements. As a parrain, you can only give your parrainage to one candidate.

These somewhat Byzantine rules were put in place to ensure that no candidate would represent narrow, regional interests (say, Corsican or Basque independence or free Breizh.) In 1976, the number of signatures was raised to 500 from the initial 100 because there were 12 candidates in the 1974 election, and that was deemed too many. It did not quite work: 10 candidates ran in the 1981 election, a record 16 in 2002 (including 3 Trotskyists!) In 2017 there were 11 candidates. We are looking at between 10 and 15 candidates in 2022: some are yet to announce while Les Républicains, the center-right party, is holding a vote to designate their champion on Dec. 4th.

Since 2012, each candidate's full list of parrainages is public, in the name of greater transparency. This can create frictions, especially in small municipalities or villages. People may not like when their politically-unaffiliated mayor, sometimes a relative or a family friend, gives his or her signature to a Trotskyist, to Marine Le Pen or to the guy who was going to bring world peace through jumping on yoga mats in lotus pose (yes, that was a thing that happened, but thankfully he couldn't get enough parrainages.)

It is a rather difficult enterprise to collect all the necessary 500 signatures. The procedure puts many candidates, even big, national figures, at a real disadvantage.

Legacy parties like Les Républicains or the Socialist Party have a plethora of elected officials at every echelon of every region, who will gladly oblige. To wit, in the last election in 2017, François Fillon gathered the most signatures (3635) while Socialist candidate Benoît Hamon came in second in parrainages with 2039 signatures. (Neither made it to the runoff, and Hamon received only a paltry 6,36% of the vote, for fifth place overall!) Half of all the 14,269 valid signatures went to either Hamon, Fillon or Macron (who did well, with 1829.)

Conversely, those candidates who do not enjoy a broad base of elected officials behind them must expend considerable time and resources to reach 500 parrainages. You have to mail thousands of letters, you have to send campaign workers to pay a visit in person and drink a glass or two of the local cordial, you have to bug each prospective parrain until their signature is banked. You have to start early, often a year ahead, and plan to get at least 750 to 800 formal promises because a lot of people will say yes and then get cold feet when the time comes to file the official form.

The signatures must be sent for verification to the Constitutional Council, the highest court in France, up to six weeks before the first round. The Council will tally the parrainages and announce the list of candidates who have made the cut no later than the fourth Friday before the election.

Some have become masters at the process: Jacques Cheminade, Lyndon LaRouche’s man in Paris, got on the ballot three times (in 1995, 2012 and 2017) and is trying hard this time as well. Arlette Laguiller of Lutte Ouvrière (one of several Trotskyist parties) holds the record with six consecutive showings (1974, 1981, 1988, 1995, 2002, 2007.) She was the first woman presidential candidate ever in 1974. Of note, there has always been at least one Trotskyist candidate on the ballot, and generally two — a testament to the commitment and the organizational skills of Trotskyist militants.

In a recent interview in Le Point, Lutte Ouvrière’s candidate Nathalie Arthaud explained that almost none of the mayors who give her their signature agree with her politics but “they do it out of pluralism and democratic consideration: they estimate that it is normal that all political currents be represented in such a milestone as the presidential election. In fact they fulfill their role to perfection.”

This year, to be on the safe side, Marine Le Pen's Rassemblement National must collect about 200 to 300 additional promises of signatures on top of its various mayors, MPs and conseillers régionaux. Similarly, per my estimate, the Greens must get 300 to 400. Both have the infrastructure and the militants, but it remains a drain. One can easily understand why such obligation has been a perennial complaint of smaller parties, who argue that it is an undemocratic exercise. The people who call the mayors and chase after them would be better employed in other capacities — distributing campaign materials at markets or at train or metro stations.

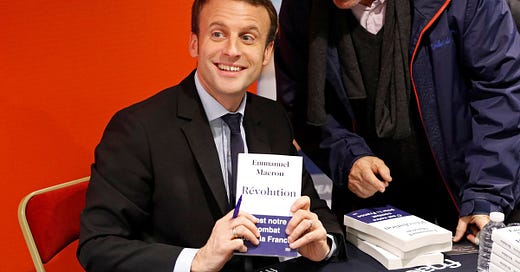

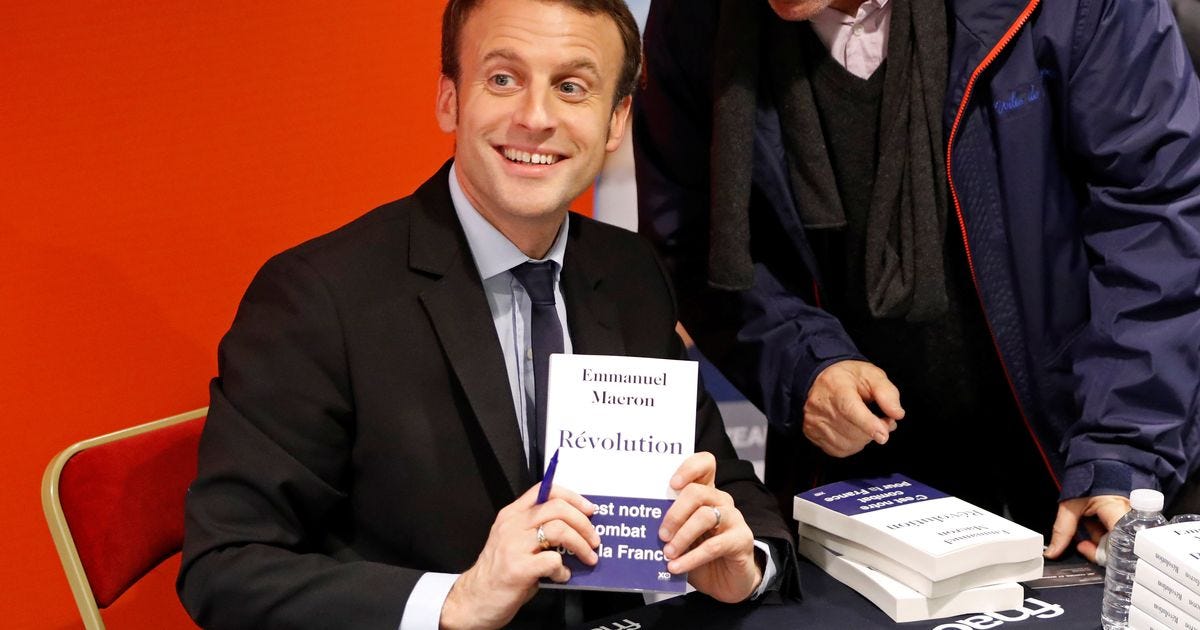

Now imagine you are a lone candidate without a party. Perhaps you will be able to rally enough elected officials from various other parties behind you because of say, media exposure and personal charisma. Perhaps, in the few months preceding the election, you and your staff can piece together some kind of movement or new party to welcome the defectors and secure their parrainages. This is the Herculean task Macron accomplished in 2017.

And what if you are a celebrity far-right provocateur, with only a skeletal cadre of fundraisers and online community managers? What if you spend a lot of your time performing racist stunts on live TV and that's your preferred way of raising awareness and drumming up support? Do you hope that a few mayors here and there will spontaneously send their parrainages, especially for someone as controversial as you affect to be? And mind you, the Trotskyists and the LaRouche guy and the other vanity candidates spend at least months and months patiently accumulating promises, sending people, following up, calling etc, etc… Unless you have been preparing in the dark for a while, and on your own dime, collecting the 500 signatures seems incredibly difficult, if not impossible.

This is to say that I am far from convinced that Éric Zemmour will be on the ballot in April 2022. I may be proven wrong, I may have missed something. I suspect that Zemmour will try to replicate Macron's end-run and peel away enough MPs or conseillers régionaux from established parties on the right and the far right. The pool is definitely not as deep as it was for Macron, who recruited from both Socialists, Bayrou's centrist MoDem and Les Républicains. Macron secured the early endorsement of caciques such as then-Lyon's mayor Socialist Gérard Collomb. That kind of permission to betray from a high level boss is the thing to watch out for. It is yet to occur in favor Zemmour.

Who will go first? And how many are willing to break ranks from their political family to offer their parrainage to such a polarizing figure? Who will risk his or her reputation and future electoral prospects to join the kamikaze candidate?

None of this easy.

— À la prochaine ! M.

Today’s song is “Tout n’est pas si facile” by Suprême NTM (1995) : the very best of French hip hop. Excellent background here: https://genius.com/20066372

One thing I forgot to put in the post: between mayors and elected grandees there are about 42,000 potential "parrains" — it's a lot.