Immigration and the sinews of history

From colonial "indigénat" to metropolitan proletariat, the legacy of France's bygone empire shapes the immigration question.

LA CAMPAGNE returns to talk about the big questions. So let's talk about immigration in France.

In a recent article, Le Monde interviews a well-off retiree from Antibes — France’s response to Palm Beach. The former property manager, 87 years old, waxes wistful: “All these migrations from European peoples did not cause any problems. The Italians, the Spanish, the Portuguese, it all worked out eventually. The problem is Islam.”

Let’s unpack our pensioners’ statement: according to INSEE’s latest official statistics, there were 6,831M immigrants in France in 2020. That’s 10,2% of the total French population. INSEE’s definition of an immigrant is a person born non-French outside of France. The French born abroad are therefore not counted as “immigrants” while naturalized foreigners are. That (French) definition is somewhat different from OECD’s, which counts citizens born abroad as foreign born. That is why France clocks at 12.8% in the following graph (OECD data from 2019).

From that chart you can see that France is squarely in the middle of the pack, behind Spain, Germany, the UK and the US.

Where it gets tricky is when you try to count the descendants of foreign-born people. In 2015, INSEE estimated that 7,3M of French people had at least one parent of foreign origin, or 11% of the total French population (that’s me, among many others). The top 5 countries of origin are Algeria at number one, then Italy, Morocco, Portugal and Spain. Europe accounts for 45% of that second-generation, the Maghreb for 31%. In 2018, Chris Beauchemin from INED (the national institute for demographic studies) mentioned the number of 40% of French people with foreign ascendance: that is, when you add second- and third-generation French citizens with at least one parent or grandparent born abroad. Fourth generation gets even more complicated, as the descendants of Belgians and Poles and Germans have melted away in the general population. In sum, this is bad news for our retiree from Antibes: the so-called “great remplacement” has already happened.

That said, in his retelling, the “problem” with immigration in France is neither immigration per se nor the precarious social conditions of the migrant proletariat, but “Islam.”

A certain conventional wisdom in France holds that Islam and the République are at best irreconcilable, at worst mortal enemies. Pundits and journalists and philosophes opine that it is an epic clash of civilizations. This is particularly baffling given France’s location on the Mediterranean sea, its long history of intense contact and commerce with Islamic kingdoms (just read Fernand Braudel!), and its more than a century of colonial rule over various Muslim populations in Africa. One would think that something, anything, would have been learned from so many years in such intimate proximity.

In addition, the distinction between “good” European immigrants to France and “Islam” is not reducible to a simple matter of creed or religious observance. For instance, the first Italians and Poles came to France in the late 19th century, at the height of the Third Republic’s kulturkampf against the Catholic Church. They were often regarded with a mix of contempt and suspicion due to their fervent Catholicism. By the 1970s, for the Portuguese masons, concierges and housekeepers, it was just contempt. Laïcité is indeed colorblind.

The source of France’s current perceptions and treatment of its Muslim residents (citizens or not) lies elsewhere. One kink of history particularly stands out. Contrary to immigrants from the Maghreb and West Africa, Southern Europeans did not carry with them the stigmas of past violence, domination and subaltern status. The French had not pillaged their countries nor had they consigned them to the corvée, head tax and other myriad iniquities of colonization. Understandably, they did not elicit comparable, if subliminal, feelings of guilt and fear of revenge from the “français de souche,” the native French — and the resulting urge to coerce, to police and to “integrate” them. In other words, if you want to understand the roots of France’s “problem” with Muslim immigrés, you must take a look at how France’s colonial subjects joined the ranks of the urban working class in the métropole.

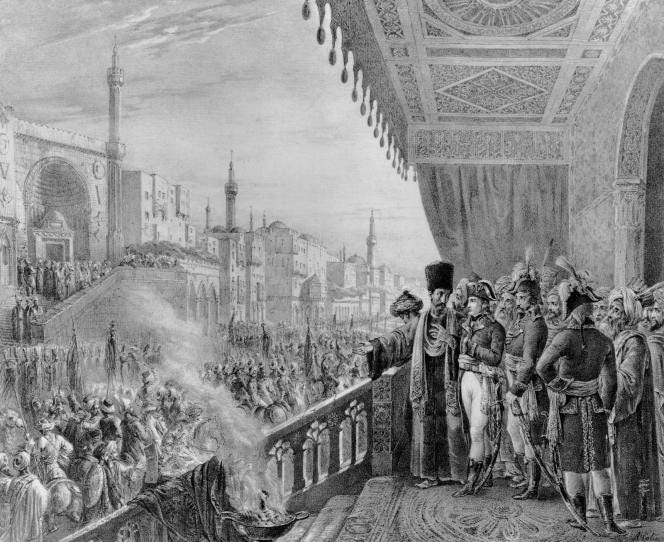

Again, it all goes back to Algeria — the crucible and the laboratory of France’s colonial empire. The conquest of Algeria was a bloody and drawn-out affair that stretched for seven decades, from the early 1830s to the early 1900s. The occupying French forces committed countless, systematic atrocities in the name of “civilizing” the purported “barbarians” and the “Arabs” who fiercely resisted them. This, by the way, is not some kind of historical secret. All of it was well-known, even at the time. Those in charge, chief among them the sordid Général Bugeaud (conqueror and governor of Algeria), boasted about their crimes to the applause of French statesmen and intellectual luminaries such as Alexis de Tocqueville (yes, that Alexis de Tocqueville).

Despite being carved into three French départements as early as 1848, Algeria was never truly pacified. Hence the invention of the “régime de l’indigénat,” cobbled together in Algeria so as to control the locals, and extended afterwards to the other French colonial possessions.

The indigénat stipulated that while the Muslim indigènes of Algeria were French, they were not citizens but subjects. They could not vote and the French Code Civil did not apply to them. Marriages, divorces, inheritance, women’s and family rights remained adjudicated according to local indigène law and by local indigène courts, mostly inspired by Islamic traditions and jurisprudence.

One can philosophize ad absurdum about supposed cultural incompatibilities between Islam and the French or the European way of life, but this misses the point entirely. From the beginning, the incompatibility was a creation of the colonizers, it was de jure. The indigénat served above all as a tool to police a majority irredentist population, that did not take lightly to their land being stolen by foreign invaders. It empowered colonial agents to mete out punishments and fines on the indigènes without due process, usually for the smallest of trifles. The pettiness and violence of the indigénat even covered colonial subjects who came to metropolitan France to fight in France’s wars and to work in France’s factories. With minor changes and accommodations along the way, the indigénat endured until 1947. To the victor the spoils, but also the perpetual headaches of their administration.

The indigénat in Algeria was a deliberate choice, or a series of choices, designed to maintain an uneasy occupation. It was the continuation of war by other means, a sort of permanent state of counter-insurgency. One could imagine a scenario where Algerian autochthones would have been granted full citizenship — but then again, they were always disloyal and always rebellious, and they were the overwhelming majority. In 1906 the census counted 4,47M Muslims for 680,000 non-Muslims in Algeria. In 1948, after the end of the indigénat, 7,68M Muslims vs 922,000 colonists (for reference, metropolitan France had an estimated population of 42M in 1946, so you can see the “problem” here.)

Throughout its occupation, France treated and even constructed Algeria’s local population as Muslims, which is to say, as enemies. I say “constructed” because a significant number of Kabyles were not in fact Muslims in the strictest sense of the word, yet they certainly were colonial subjects. I also say “constructed” because France could decide to draw the line where it saw fit, thereby exempting some colonial subjects from the indignities of the indigénat regime. In theory, any indigène could claim French citizenship by abjuring Islamic law. In practice, only about 2000 did so between 1880 and 1920. More significantly, France granted full citizenship to Algerian Jews in 1870. By culture, language and traditions, Algerian Jews were Arabs and Berbers. They had nothing in common with the Sephardic bankers and the Ashkenazi industrialists who had championed their cause back in the métropole. They were bestowed French citizenship in spite of their perceived backwardness, further relegating other Algerians, their friends, their neighbors, their cousins sometimes, to the arbitrary of colonial oppression.

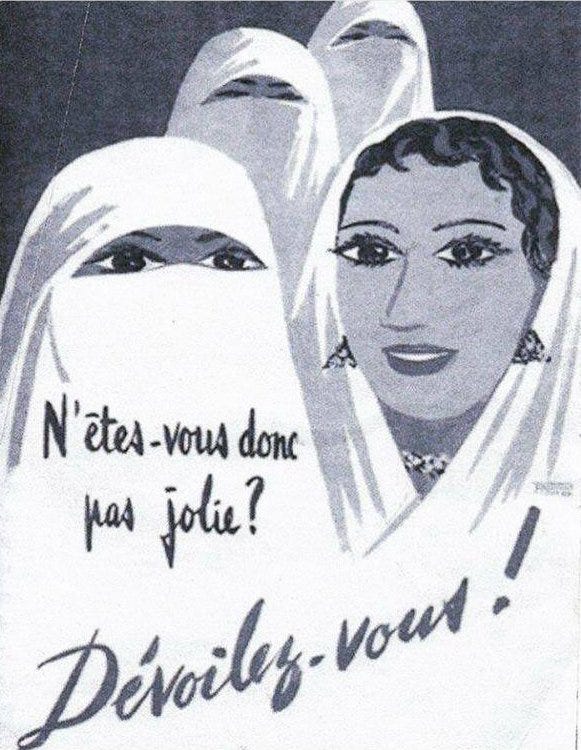

These are not mere curiosities of colonial history. These are deep and ancient sinews that shape France’s attitudes and policies toward its Muslim citizens. Consider for instance the recurring outcries about Muslim women wearing hijab in public (aka teenage girls attacking France’s sacrosanct laïcité). These periodic moral panics take on a very different resonance once you hear that during the Algerian War, in between torture sessions, the French army would conduct ceremonies of “unveiling,” where more or less coerced Algerian women took off their veils and proclaimed their loyalty to France and their “emancipation.” (On that topic you can watch a short documentary on Le Monde’s Youtube channel, with University of Ottawa historian Ryme Seferdjeli.)

But it does not stop at this pathetic racist kabuki. As it turned out, France needed its colonial subjects more than they needed her. At the end of World War II the country found itself on its knees and short on manpower for reconstruction. Along with others (Italians, Portuguese, Moroccans, etc) Algerians moved to metropolitan France en masse. Per sociologist Mohand Khelil, the Algerian population in France rose from 35,000 in 1946 to 220,000 in 1954. This was not a “migration,” as Algeria was still formally a part of France. Men would cross the Mediterranean to toil for two or three years, sending money home to help, and then they would go back to their wilayat while others would take their place.

As the war of independence raged in Algeria, workers continued to flock to the métropole. By the end of the of the conflict in 1962 they were 350,000. No need to mention that this mostly male, young and urban proletariat constituted a huge threat for the French State, which treated them as insurgents and terrorists in waiting. At the same time, the FLN, Algeria’s liberation movement, was deeply embedded among Algerian workers in France. It organized demonstrations, collected the revolutionary tax and also purged and assassinated supporters of competing parties. It was guerrilla warfare on French soil. Sixty years ago, on October 17, 1961, the French police killed more than a hundred Algerian demonstrators and threw their bodies in the Seine river. The Algerians in France were indeed the ennemi de l'intérieur, the internal enemy, and worst! they eventually won out.

The Algerian war was the most violent and the most destabilizing. As we saw in a previous post, it hastened the fall of the Fourth Republic and brought De Gaulle back to power. But it was only one episode in France’s sweeping decolonization process. By 1962 France had lost almost all of its empire, except for marginal places such as the Comoros, Mayotte and a few territories in the Caribbean and the Pacific. Yet, it still desperately needed workers to fuel its economic boom. The Trente Glorieuses, post-war France’s three decades of breakneck growth and prosperity, would not have been glorious at all, let alone possible, without the massive influx of foreign workers.

France tapped its old colonies, now independent nations, to recruit former indigènes to work in construction and in factories. Major French companies would send agents to Morocco and Senegal and Mali to hire people by the thousands. And when that wasn't enough France delivered residency papers on the spot, at the border, to the Portuguese who fled military conscription in Salazar's crumbling dictatorship. In 1975, the Portuguese were the largest foreign community in France (estimated at 950,000). According to INSEE’s figures, France’s immigrant population doubled between 1946 and 1975, from 1.9M to 3.8M. In 1968, at Renault’s gigantic Billancourt automobile plant just outside of Paris, 7,000 of the 21,000 employees were immigrants.

Foreign workers settled where the jobs were, in and around major urban areas. That social geography persists to this day: Paris, Lyon and Marseille concentrate the descendants of those who came to rebuild France, as well as the more recent arrivals. Rural and exurban France, the France périphérique from where the gilets jaunes protesters hail, did not attract many immigrants precisely because it had little to offer in the way of economic opportunities.

Work conditions and everyday life were extremely harsh for migrant workers. At first they lived in rings of large, makeshift slums on the outskirts of the big cities (e.g. Algerians in the Nanterre slums, Portuguese in the Champigny-sur-Marne slums). In 1964 there were as many as 89 slums in the Paris banlieues. Later, people were relocated to “social” housing. The low-rent apartment complexes were owned and operated by municipalities and became known as les cités in a somewhat dismal nod to Le Corbusier’s functionalist utopia.

Fast forward to today: the economic crisis of the 1970s and 1980s led to deleterious de-industrialization. Those who had come to France to find work fell on hard times, as did their children. Blight and poverty gripped the banlieues where the immigrant proletariat had settled. Mass unemployment, a perennial problem in France since the mid-1970s, hit these areas particularly hard. At its heart, the strife in the banlieues is a function of social and economic adversity. Add to the challenges of unemployment systemic racism, the legacy of the indigénat and decolonization, and you end up in an almost intractable situation.

Or do you?

The following dataset from INSEE tells a remarkable story. It graphs the educational attainments of the descendants of immigrants by geographic origin. The bigger the light blue bar, the higher the proportion of advanced university or technical diplomas (the word “Bac +2” means high school graduation plus two years.)

You can see that the descendants of African immigrants (Maghreb and West Africa) beat out the natives in high school graduation and advanced degrees. They are the group where the fewest do not complete high school. This happened in spite of all the difficulties, social, racial and otherwise, that these children had to overcome.

You will notice that the children of European migrants do not pursue university diplomas in the same proportion. Sociological factors and — yes — cultural proclivities account for that (in particular, girls and young women of Portuguese descent tend to drop out early after high school.) It is as if the system worked too well for the sons and daughters of the former indigènes, who truly embraced the French model of social ascension through education. They bought into France’s romance of Republican equality. They used it to their advantage. If that is not integration, then I don’t know what is.

Perhaps, then, the immigration question in France can be reframed outside of tired and noxious notions of civilizational conflict. The real friction in French society appears to be between the young, striving and educated French of diverse backgrounds and their native peers. They are competing for jobs and status that used to be the exclusive purview of the français de souche, to use the racists’ parlance. After losing Algeria and the colonies, the good old French are now losing ground on their own turf, to their former subaltern, Muslim subjects. That’s of course the downcast and zero-sum view of things, which prospers on widespread fears of decline and social déclassement.

The optimistic view is that over time, even the hardest of social problems can be solved through education and public investments.

A la prochaine! — M.

Today’s song is Rachid Taha and Carte de Séjour’s raï cover of Charles Trénet’s classic “Douce France.” It’s hard to convey how meaningful that band and that hit song were to a lot of folks in the 1980s.

"even the hardest of social problems can be solved through education and public investments. "

this story is to a large extent about the way full employment helps almost everything else, isn't it?